A rhino conservation exercise at Nakavango was an extremely emotional experience for volunteer Samirika Castelle.

Watch the video, and read her story below:

It was going to be another frosty morning for the Nakavango conservation programme volunteers in the Victoria Falls Private Game Reserve.

This morning was going to be special. I would witness an event that would help me gain a better understanding of wildlife conservation. On the previous evening, myself and the other volunteers had sat by the pool soaking in the last rays of the African sun, when we were told to be ready at 7am by Justine, our red-headed Zimbabwean den mother, or to use her official title, the Nakavango Volunteer Manager.

Justine was clear about how stressful it was going to be, and how our job as volunteers was to stay out of the way unless our help was required. But most importantly we were asked to attend because it was going to be an invaluable educational experience. So there we all were ripe and ready by 6:30 am on the verandah, clutching on to our warm cups of tea and coffee waiting for the word “ready”.

Struggling to contain the anticipation we picked up our rucksacks, made sure our phones and cameras were on full charge and gathered around the safari vehicles parked outside our accommodation. Soon after we were given another briefing by Dean, our straight-talking, yet kind-hearted and deeply knowledgeable team leader.

“We are relocating Kushinga, a seven-year-old male rhino from Nakavango, to Imire Private Game Reserve where he will get lots of girls and live a long and happy life,” he explained.

Suddenly I was skittish as I didn’t know what to expect. I thought about all that could go wrong instead of focusing on the positive side of things.

As Dean continued his briefing, the helicopter pilot arrived and I felt the nerves kicking in again, not for myself but for Kushinga. After waiting for what felt like an eternity, we were given the go-ahead. Suddenly I was without thought, the initial nerves had all but faded. I was looking forward to this, it was the best future for Kushinga, and I knew I would be happy to see him being taken to his new home.

I was full of smiles, as was everyone else. All the volunteers took their seats in two separate vehicles and we followed the veterinarians, the pilot and other members of the management team into the bush.

The sun roared in the sky. As a warm breeze danced around me, I felt optimistic. After driving for a short time, we came to a stop at a nearby game rangers’ site where the helicopter was grounded. The helicopter was smaller than I expected. I watched the senior veterinarian, 72-year-old Dr Chris Foggin board the helicopter along with the pilot.

Ian, the game reserve manager, or as I like to think of him. the “walking talking encyclopaedia of all things wild”, told us that Kushinga suffers from a genetic deficiency where his back legs are too skinny and weak. Kushinga would not be able to defend himself against the other males in the park so moving him was for his own good.

In his new home, there would be nutritious vegetation because there is higher rainfall. There would be females he can mate with, because there would be no competition from other males. Just as I was swallowed into a state of sadness despite all the good reasons behind Kushinga’s relocation, we were ready to move again.

The helicopter took off. Kushinga had been spotted happily wandering around the plains, grazing andcompletely unaware of the events that were about to unfold. The sound of the rotating helicopter blades added to my already unsteady nerves. We boarded the safari vehicles one more time.

After driving for a few minutes, I heard “there he is, he’s down”. The helicopter hovered a few inches above the treetops. Red dust and dry leaves circled us in a tornado as the helicopter landed some feet. Kushinga had been darted and sedated without trouble thanks to the skills of the veterinarian.

I couldn’t spot Kushinga at first. As soon as the vehicles came to a halt, I jumped out into the blistering heat, and then I saw him. Kushinga lay on his side surrounded by wildlife professionals. He had a cover around his eyes and mouth; his ears were plugged with what looked like cotton wool so he couldn’t hear the world around him as he slept.

There were tanks of oxygen, water pumps and various other medical paraphernalia. Water was splashed over his skin to keep him cool. But none of that mattered. When my eyes focused on Kushinga, my heart held skipped a beat and my throat clogged with sorrow and agony. I had never seen Kushinga before but It felt as if I had known him my whole life. He was my family, someone I loved dearly, and he was helpless.

It wasn’t my eyes that shed tears it was my soul. I wanted to run to Kushinga, take him in my arms, stroke his cheeks, kiss his forehead and tell him everything was going to be fine. But I couldn’t. I walked closer and saw the veterinarian carry out medical checks.

Intermittently, Kushinga took a deep breath in and exhaled out. I stopped sobbing and took out my phone to take some pictures. It felt disrespectful, how could I take pictures of this? I was a hypocrite. But I could use these to teach others back home of the trouble and stress game reserve staff go through to ensure the future of these animals.

I held back my emotions until I heard the growling, gyrating sound of a chainsaw. It sent shivers up and down my spine. Kushinga was about to be dehorned. My heart couldn’t take the anguish, this was what true heartbreak felt like. Any joy I had left dispersed and disappeared. Tears fell faster than I could stop them.

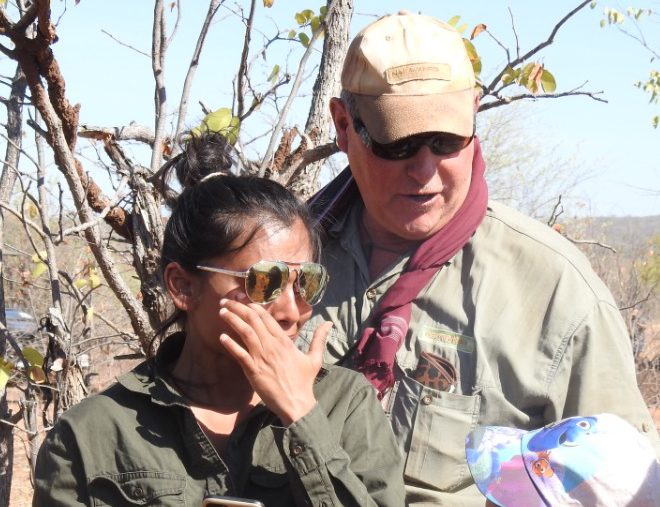

How can we do this? What right do we have to disfigure a wild animal? Who gave us permission to be so arrogant? But then I thought about the reasoning behind it. It was to protect Kushinga. He was now not as “valuable” to poachers. How can we put a price on the innocent and the defenceless? Justine put her arms around me as my tears kept rolling.

“Is he in pain, will he feel anything?” I aimlessly searched for answers from Justine.

“He’s going to be fine,” she reassured me. “All these guys around him care about Kushinga more than they care about anything else. He’s not in any pain, the horn is sawn off just before the blood vessels, it’s just like cutting off a nail.”

For a reason I couldn’t explain, Justine’s words cut through me like a knife. My heart finally caught up and I felt it beat painfully against my chest. As I tried to reason with myself I knelt down. My hands shook in despair as I held my phone in front of me trying to capture a moment I would rather forget.

As the chainsaw cut through the horn, I realised how unforgiving and unfair the world truly is. Once the horn had been removed I walked away and used the back of my hand to wipe away my tears.

The horn weighed 0.9kg, if put on the market it would be worth around $USD 85,000. But the horn was placed in a black bin bag and taken away to be handed to the Zimbabwean government, where it would be stored in a warehouse along with other wildlife property.

After I gathered my thoughts I returned to Kushinga, because it was time to wake him up. The veterinarian administered the antidote. All eyes were on him. The professionals held on to Kushinga to help him into the metal carrier that would transport him to his new home. It was a nineteen-hour journey.

It was over quickly, but only because of the dedication and expertise of all those who were involved. The emotions were still raw and I was embraced by the other volunteers who shared the same feelings as I did. The carrier was attached to a tractor and the site was cleaned and cleared.

All the vehicles followed the tractor to a workshop site where Kushinga’s carrier was hauled on to the back of a lorry. During the journey, Kushinga would be monitored and cared for by his new family, the management at Imire.

Watching the lorry leave Nakavango, I prayed for Kushinga to be happy and healthy in his new home.

Images: Suiyi Li

Video: Genevieve Detering